6. Harmonics

Page 1 of 1

6. Harmonics

6. Harmonics

Harmonics are one of the biggest reasons why one instrument sounds different than the next. They are why scales work. They are the answer to a lot of questions.

Every instrument produces a shit-load of frequencies when you play any note. The note we say that instrument is playing is the most prominent one, which is almost always the lowest one. This is called the "first harmonic," or more commonly, "the fundamental." Instruments have different tones than each other because they produce different combinations of harmonics after the fundamental. You can see this if you use that frequency analyzer plug-in on several different instruments. Another cool trick is to plug a guitar into it and flip through different pickups. You can see that the bridge pickup has more harmonics than the neck pickup. Mellow sounds (woodwinds, xylophone, neck pickups) usually have more fundamental and less harmonic. Twangy or shrill sounds have lots of harmonics.

DISTORTION:

Distortion adds lots of harmonics, more and more as the gain goes up. Tube amps sound sweet because they add more even-order harmonics (i.e. the 2nd, 4th, 6th) while solid state amps are more random. Tape saturation adds third order harmonics (3rd, 6th, 9th) and sounds sweet because there is a nice order.

HARMONICS ON STRING INSTRUMENTS:

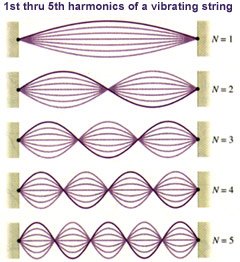

The way different harmonics vibrate on the same object is easy to see on a string.

This picture shows a guitar string and the way the first five harmonics would look on it. The spots that look twisted together, where the string is at 0 are called nodes, the spots where the string is moving the most are called anti-nodes. They are fixed positions for each harmonic, meaning the node for the second harmonic is always half-way down the string.

All of those waves of motion exist on the string at once, so the actual motion is a sum of all those, but they are all happening. So say that's my A string open. The fundamental would be 220Hz, and we would use that to label it as an A. Simultaniously, the second harmonic would be vibrating twice as fast (440Hz) and a little quieter. The third harmonic would be 660Hz, four would be 880Hz, and five would be 1100Hz.

The easiest harmonics to play on guitar are on the 12th fret, played by lightly touching the string and not pressing it down to the fret. The reason this has a higher, chimey tone is because, since the 12th fret is at the string's mid-way point, putting your finger there mutes all the odd-order harmonics (because they have anti-nodes there), but it doesn't affect the even-order harmonics (because that spot is a node for them, the string wouldn't be moving there anyway, so you're finger cannot stop it.) Other harmonics at the 4th, 5th, or 7th frets create different combinations of harmonics that result in their unique tones.

SUB-HARMONICS:

Occasionally there are harmonics below the fundamental. This really only comes up with electronic instruments. Many synths will give you options to add a quieter octave-down pitch to your tone, sometimes I've heard guitar cabinets resonate at notes lower than the guitar was actually playing. These are called sub-harmonics. If you see an effect called a "sub-harmonic generator" or something like that, its pretty much a super-octaver pedal, designed more for kicks and basses, stuff that you really want to rumble.

RELATIONSHIPS OF INTERVALS:

If two pitches are an octave apart, it is because one frequency is a power of two of the other. Meaning since 440Hz is A, 220Hz is A an octave below, 880Hz is an octave above, 110Hz, 55Hz, 1760Hz are also A.

There are mathematical relationships between all the intervals in the chromatic scale. The frequencies of a perfect 5th, for example, have a ratio of 3:2. The rest of the intervals are as follows:

Min 2nd 16:15

Maj 2nd 9:8

Min 3rd 6:5

Maj 3rd 5:4

4th 4:3

Tritone 7:5

Min 6th 8:5

Maj 6th 5:3

Min 7th 7:4

Maj 7th 15:8

Octave 2:1

With the exception of the octave, all the numbers are rounded. They're slightly off the perfect fractions so you can play in all 12 keys without changing instruments. Before Bach it was otherwise.

But for all intents and purposes, those are the numbers. The simpler the ratio the more harmonious the two tones sound together. Harmony is essentially playing two notes whose rhythms of vibration synchronize in some way.

MUSICAL RELATIONSHIP OF HARMONICS:

Back to the different frequencies occurring on the same guitar string...

So if I hit my A string and I get a fundamental of 220Hz, a 2nd of 440Hz, 3rd 660Hz, 4th 880Hz, and 5th 1100Hz, it turns out all those harmonics are harmonic intervals of the fundamental. 440 is double, so it's an octave (same A as 2nd fret on G). 660 is at a 3:2 ratio with 440, so its a fifth above that octave (high E string). 880 is double the last octave, so its another octave of A (7th fret high E). 1100 is at a 5:4 ratio with the last one, so its a major third above it (Db @ 11th fret). There are also higher frequencies occurring. If you hit the 12th fret harmonic on the string, you would hear 440, 880, 1320..., but no 220, 660, 1100... At the seventh fret you would hear the 3rd, 6th, 9th... harmonics.

BOTTOM LINE!!!:

I think the biggest thing to take away from the idea of multiple simultaniously occurring harmonics, is to stop thinking of sounds as one sound. Every sound you hear is a collection of sounds.

Every instrument produces a shit-load of frequencies when you play any note. The note we say that instrument is playing is the most prominent one, which is almost always the lowest one. This is called the "first harmonic," or more commonly, "the fundamental." Instruments have different tones than each other because they produce different combinations of harmonics after the fundamental. You can see this if you use that frequency analyzer plug-in on several different instruments. Another cool trick is to plug a guitar into it and flip through different pickups. You can see that the bridge pickup has more harmonics than the neck pickup. Mellow sounds (woodwinds, xylophone, neck pickups) usually have more fundamental and less harmonic. Twangy or shrill sounds have lots of harmonics.

DISTORTION:

Distortion adds lots of harmonics, more and more as the gain goes up. Tube amps sound sweet because they add more even-order harmonics (i.e. the 2nd, 4th, 6th) while solid state amps are more random. Tape saturation adds third order harmonics (3rd, 6th, 9th) and sounds sweet because there is a nice order.

HARMONICS ON STRING INSTRUMENTS:

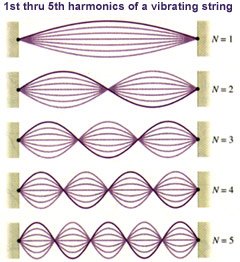

The way different harmonics vibrate on the same object is easy to see on a string.

This picture shows a guitar string and the way the first five harmonics would look on it. The spots that look twisted together, where the string is at 0 are called nodes, the spots where the string is moving the most are called anti-nodes. They are fixed positions for each harmonic, meaning the node for the second harmonic is always half-way down the string.

All of those waves of motion exist on the string at once, so the actual motion is a sum of all those, but they are all happening. So say that's my A string open. The fundamental would be 220Hz, and we would use that to label it as an A. Simultaniously, the second harmonic would be vibrating twice as fast (440Hz) and a little quieter. The third harmonic would be 660Hz, four would be 880Hz, and five would be 1100Hz.

The easiest harmonics to play on guitar are on the 12th fret, played by lightly touching the string and not pressing it down to the fret. The reason this has a higher, chimey tone is because, since the 12th fret is at the string's mid-way point, putting your finger there mutes all the odd-order harmonics (because they have anti-nodes there), but it doesn't affect the even-order harmonics (because that spot is a node for them, the string wouldn't be moving there anyway, so you're finger cannot stop it.) Other harmonics at the 4th, 5th, or 7th frets create different combinations of harmonics that result in their unique tones.

SUB-HARMONICS:

Occasionally there are harmonics below the fundamental. This really only comes up with electronic instruments. Many synths will give you options to add a quieter octave-down pitch to your tone, sometimes I've heard guitar cabinets resonate at notes lower than the guitar was actually playing. These are called sub-harmonics. If you see an effect called a "sub-harmonic generator" or something like that, its pretty much a super-octaver pedal, designed more for kicks and basses, stuff that you really want to rumble.

RELATIONSHIPS OF INTERVALS:

If two pitches are an octave apart, it is because one frequency is a power of two of the other. Meaning since 440Hz is A, 220Hz is A an octave below, 880Hz is an octave above, 110Hz, 55Hz, 1760Hz are also A.

There are mathematical relationships between all the intervals in the chromatic scale. The frequencies of a perfect 5th, for example, have a ratio of 3:2. The rest of the intervals are as follows:

Min 2nd 16:15

Maj 2nd 9:8

Min 3rd 6:5

Maj 3rd 5:4

4th 4:3

Tritone 7:5

Min 6th 8:5

Maj 6th 5:3

Min 7th 7:4

Maj 7th 15:8

Octave 2:1

With the exception of the octave, all the numbers are rounded. They're slightly off the perfect fractions so you can play in all 12 keys without changing instruments. Before Bach it was otherwise.

But for all intents and purposes, those are the numbers. The simpler the ratio the more harmonious the two tones sound together. Harmony is essentially playing two notes whose rhythms of vibration synchronize in some way.

MUSICAL RELATIONSHIP OF HARMONICS:

Back to the different frequencies occurring on the same guitar string...

So if I hit my A string and I get a fundamental of 220Hz, a 2nd of 440Hz, 3rd 660Hz, 4th 880Hz, and 5th 1100Hz, it turns out all those harmonics are harmonic intervals of the fundamental. 440 is double, so it's an octave (same A as 2nd fret on G). 660 is at a 3:2 ratio with 440, so its a fifth above that octave (high E string). 880 is double the last octave, so its another octave of A (7th fret high E). 1100 is at a 5:4 ratio with the last one, so its a major third above it (Db @ 11th fret). There are also higher frequencies occurring. If you hit the 12th fret harmonic on the string, you would hear 440, 880, 1320..., but no 220, 660, 1100... At the seventh fret you would hear the 3rd, 6th, 9th... harmonics.

BOTTOM LINE!!!:

I think the biggest thing to take away from the idea of multiple simultaniously occurring harmonics, is to stop thinking of sounds as one sound. Every sound you hear is a collection of sounds.

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum|

|

|